Expanding into China offers immense opportunities, but navigating the country’s strict advertising regulations can be a complex challenge. Compliance is not just a legal requirement; it’s also crucial for building trust and credibility with local consumers. Failing to comply, however, can threaten the continuity of your advertising campaigns and expose your business to serious legal consequences. According to Zhong Lun Law Firm, non-compliance with China’s advertising regulations can result in:

-

- Administrative Penalties: Including warning, fines, confiscation of illegal earnings, or orders to suspend ad campaigns, etc.

- Civil Liabilities: If the ad content violated someone’s rights and interests, such as the right to privacy and portrait rights, affected consumers or competitors may file compensation claims.

- Joint Liability: Advertisers, publishers, and brand ambassadors may all be held accountable.

- Reputational Crisis and Market Access Restrictions: A tarnished brand image can negatively impact sales and overall reputation. In the worst-case scenario, in addition to fines, market regulatory authorities may also revoke business licenses.

- Criminal Liability: Severe cases may result in criminal charges, where the responsible individuals will bear criminal liability in accordance with the law.

Cultural Barriers, Legal, and Linguistic in Advertising

When entering China’s market, foreign companies often face unique challenges that can derail their advertising strategies if not addressed properly. Let’s explore these barriers with practical examples to illustrate their significance.

1. Cultural Barriers

Advertising success relies heavily on understanding local cultural norms. Misaligned messaging not only fails to resonate with Chinese consumers but can also lead to unintended offense. For instance

-

- Comparative Advertising: In international markets, it’s common for brands to compare their products to competitors’ or use sarcasm to stand out. However, China’s Ad Law strictly prohibits ads that disparage other products or services. For example, under Article 69.3: If advertisers, advertising operators, or advertising publishers violate the provisions of this law and engage in any of the following infringing acts, they shall bear civil liability in accordance with the law, including disparaging the goods or services of other producers or operators. This means that the infamous Pepsi commercial, where a child stepped on Coca-Cola cans to purchase a can of Pepsi, would have been subject to legal consequences in China.

- Symbolic Sensitivities: Colors, numbers, and phrases often carry deep cultural significance in China, which, while not regulated under China’s Advertising Laws, can still greatly impact the success of a campaign. For instance, using the number “4,” which sounds similar to the word for “death” in Chinese, does not violate any legal provisions but could alienate your audience and lead to a public relations disaster.

This impact can be even more detrimental if the campaign runs during a festive season, such as Chinese New Year or the Mid-Autumn Festival, when cultural symbols of prosperity, harmony, and joy are particularly important. Overlooking these sensitivities could damage your brand image and derail the effectiveness of your advertising efforts.

Examples of Missteps:

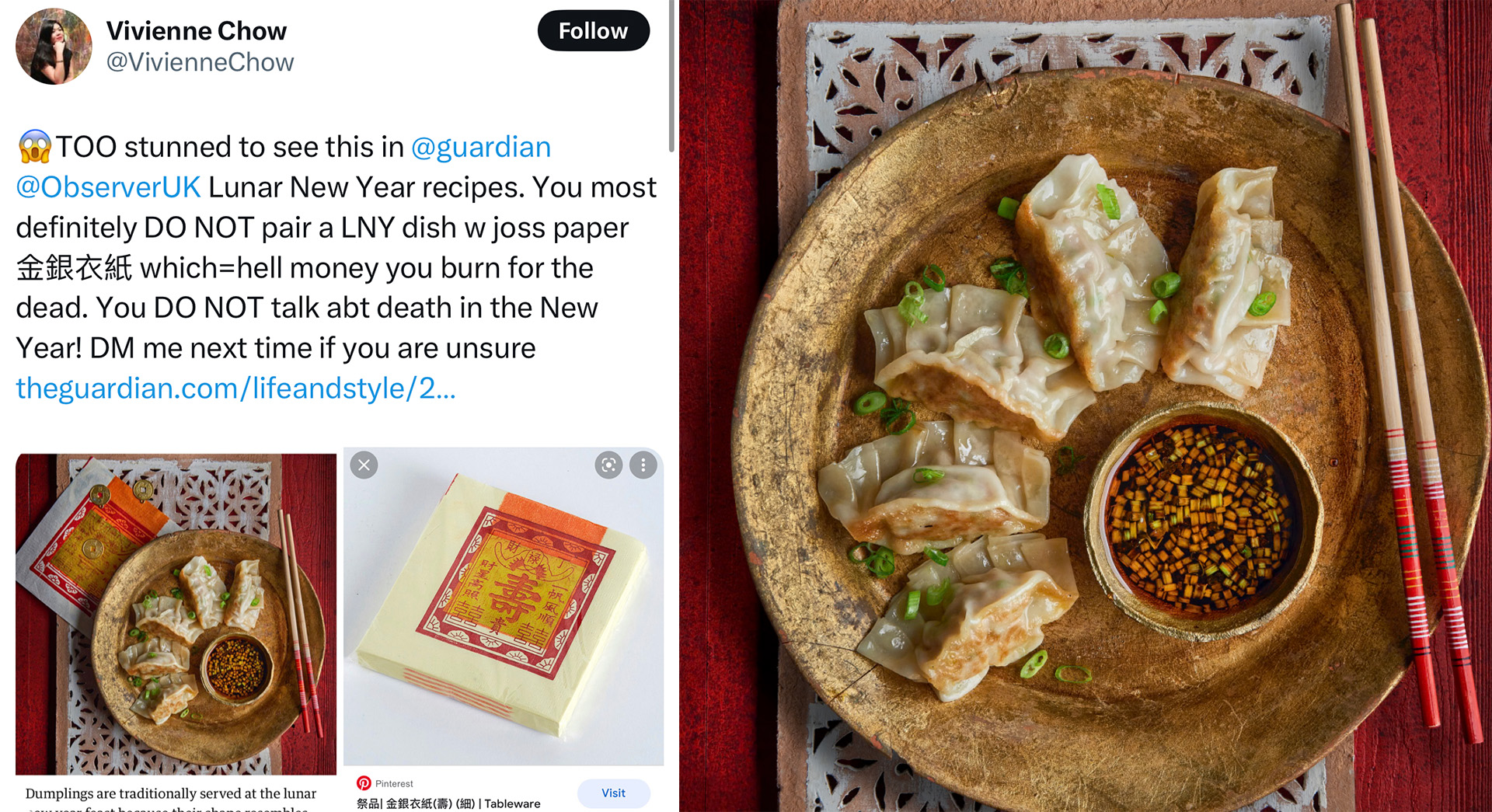

- The Guardian’s The Observer: In a Lunar New Year recipe article, The Observer used joss paper, traditionally burned in Chinese funerals, as a decorative element in its photos. This oversight was widely criticized as inauspicious and disrespectful, especially given the emphasis on good fortune and positive symbolism during the Lunar New Year. Although the publication has since altered the photo, the misstep left a lasting negative impression, particularly among mainland Chinese audiences, where cultural respect holds significant importance.

- Balenciaga’s “Offensive Ads” Controversy: In a campaign for Qixi Festival (Chinese Valentine’s Day), Balenciaga introduced a collection of bags designed specifically to celebrate this culturally significant occasion and to appeal to Chinese consumers. However, the promotional visuals faced significant backlash. The ads featured models styled in oversized clothing, posed in cluttered and unflattering environments, which many Chinese consumers found offensive and disrespectful. Critics argued that the campaign relied on outdated stereotypes of Chinese culture, presenting a distorted and unrefined image that failed to align with the modern, sophisticated tastes of Chinese audiences.“The ad campaign is downright ugly and tasteless. It reminds me of the style used by photography studios in rural China in the 1990s,” a Weibo user wrote in a post (originally in Chinese), which has received nearly 630,000 likes as of the published date of the article. (The China Project)

- Dolce & Gabbana’s Cultural Misstep and Racism Controversy: In 2018, Dolce & Gabbana launched a promotional campaign ahead of a planned Shanghai fashion show, featuring a Chinese model awkwardly eating Italian delicacies like pizza and pasta with chopsticks. The campaign, intended to highlight cultural fusion, instead drew backlash for perpetuating stereotypes and mocking Chinese culture. Matters worsened when viewers noticed sexist undertones in the narration directed at the model.

The situation escalated further when Vietnamese model Michaela Phuong Thanh Tranova shared screenshots of private Instagram messages from Stefano Gabbana, co-founder of the brand, which contained offensive and racist remarks about China. The leaked messages ignited a global uproar and sparked the hashtag #BoycottDolce on Chinese social media platform Weibo. Many of the show’s participating models publicly announced their withdrawal. According to Diet Prada, the social media watchdogs of the fashion industry, Shanghai government canceled the event just hours before it was scheduled to start. (Vox)

2. Legal Barriers

China’s advertising laws are among the strictest in the world, with regulations that differ significantly from international standards. These differences are particularly evident in sectors such as healthcare, education, and finance, where China enforces more stringent controls. Below are examples that illustrate how Chinese advertising laws can differ from global norms, and how brands must navigate these regulations carefully.

-

- Healthcare: In China, advertisements for medicines and health-related products are subject to strict regulations. Article 18 of the advertising law mandates that advertisements for health supplements must prominently state, “This product cannot replace medicine.” This requirement ensures that consumers are clearly informed about the limitations of these products, preventing them from being misled into believing that supplements can serve as substitutes for actual medical treatments.

- Education: In some foreign markets, education service providers may advertise score improvements without facing strict legal repercussions, as long as the marketing message isn’t overtly misleading. However, in China, such claims are prohibited under Article 24: Advertisements for education and training services must not include explicit or implied guarantees regarding the effectiveness or outcomes of the services. This regulation is aimed at preventing unrealistic expectations and protecting consumers.

- Personality Rights: In China, advertisements that feature an individual’s likeness, name, or other personal identifying characteristics must comply with strict consent requirements. Article 33 of the advertising law mandates that advertisers obtain written consent from individuals before using their likeness, name, or other personal characteristics in advertisements. This rule is especially stringent on platforms like WeChat, where they may request written consent along with proof of identity, such as a resident card, during the ad review process. Failure to meet these requirements could result in ad rejection.

3. Linguistic Barriers

Language barriers extend beyond simple translation errors to deeper cultural miscommunications. Poorly translated ads not only fail to connect with the target audience but can also lead to legal trouble.

-

- Use of Absolute Terms: While it’s common in English advertising to describe a product as “unique” or “the best,” translations like “独一无二” or “最好” violate China’s advertising regulations, which prohibit the use of absolute terms.

- Ambiguity in Tone: Casual humor or wordplay in English such as puns may not translate well into Chinese, potentially leading to unintended interpretations or in a worst case scenario: legal scrutiny.

Why It’s Worth Getting It Right

Adhering to China’s advertising regulations not only avoids legal trouble but also enhances your brand’s reputation and trustworthiness in a highly competitive market. Success in navigating these regulations can set your company apart and pave the way for long-term growth.

Ready to Expand in China?

If you’re looking for guidance from experts experienced in helping MNCs succeed in China’s market, chat with us today!